I didn’t intend to do another “found” poem from a Trump speech, but the following passage, sent by my friend Sallie Reynolds, was irresistible. It’s one single sentence.

You choose: read it first, or read the two poems below it first: by me and Winkie Ma, a high-school senior whom I mentor in a writing program. Found poetry was one of our assignments. I brought the passage to a mentoring session and each of us tackled it.

Here goes, hold on to your rational mind:

Look, having nuclear—my uncle was a great professor and scientist and engineer, Dr. John Trump at MIT; good genes, very good genes, OK, very smart, the Wharton School of Finance, very good, very smart—you know, if you’re a conservative Republican, if I were a liberal, if, like, OK, if I ran as a liberal Democrat, they would say I’m one of the smartest people anywhere in the world—it’s true!—but when you’re a conservative Republican they try—oh, do they do a number—that’s why I always start off: Went to Wharton, was a good student, went there, went there, did this, built a fortune—you know I have to give my like credentials all the time, because we’re a little disadvantaged—but you look at the nuclear deal, the thing that really bothers me—it would have been so easy, and it’s not as important as these lives are (nuclear is powerful; my uncle explained that to me many, many years ago, the power and that was 35 years ago; he would explain the power of what’s going to happen and he was right—who would have thought?), but when you look at what’s going on with the four prisoners—now it used to be three, now it’s four—but when it was three and even now, I would have said it’s all in the messenger; fellas, and it is fellas because, you know, they don’t, they haven’t figured that the women are smarter right now than the men, so, you know, it’s gonna take them about another 150 years—but the Persians are great negotiators, the Iranians are great negotiators, so, and they, they just killed, they just killed us.

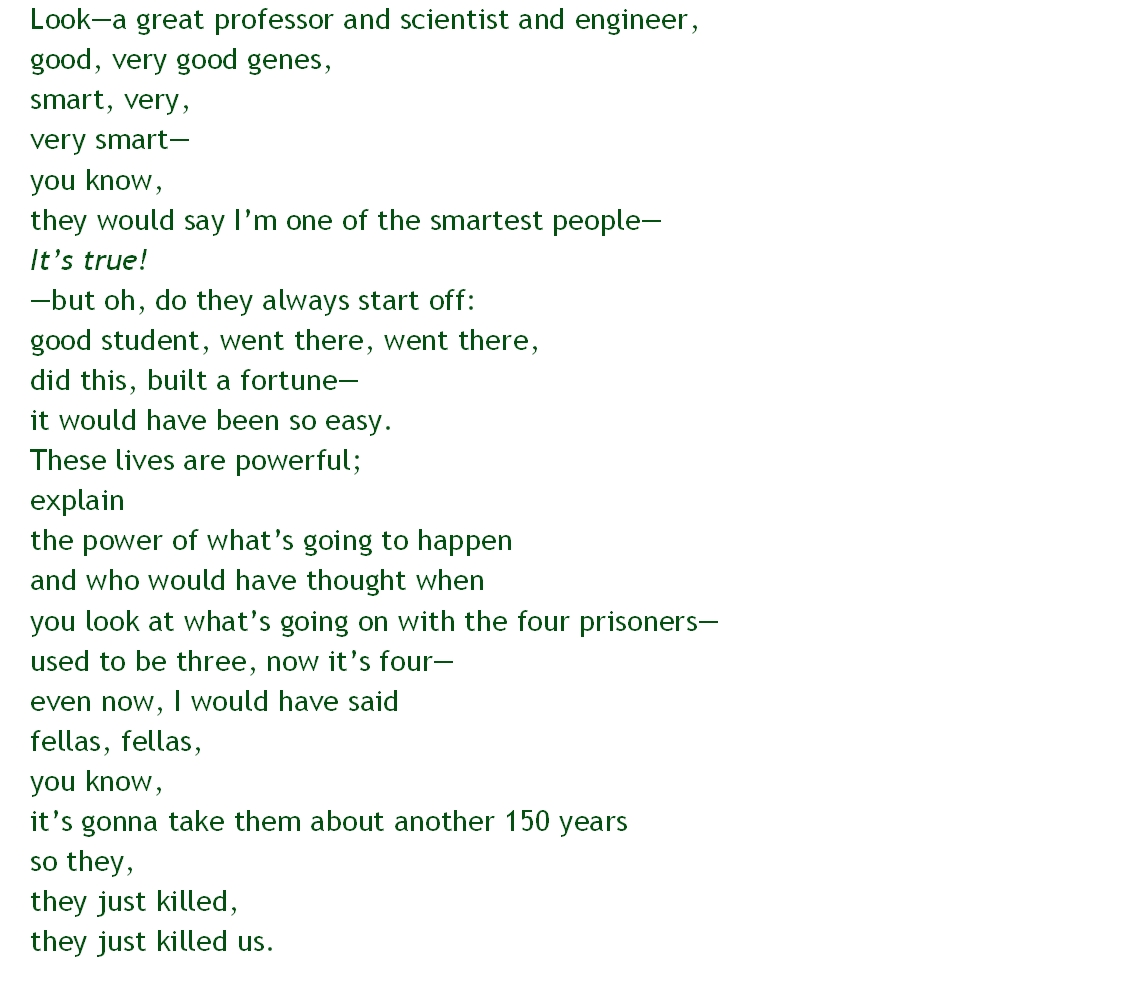

Here’s Winkie’s poem:

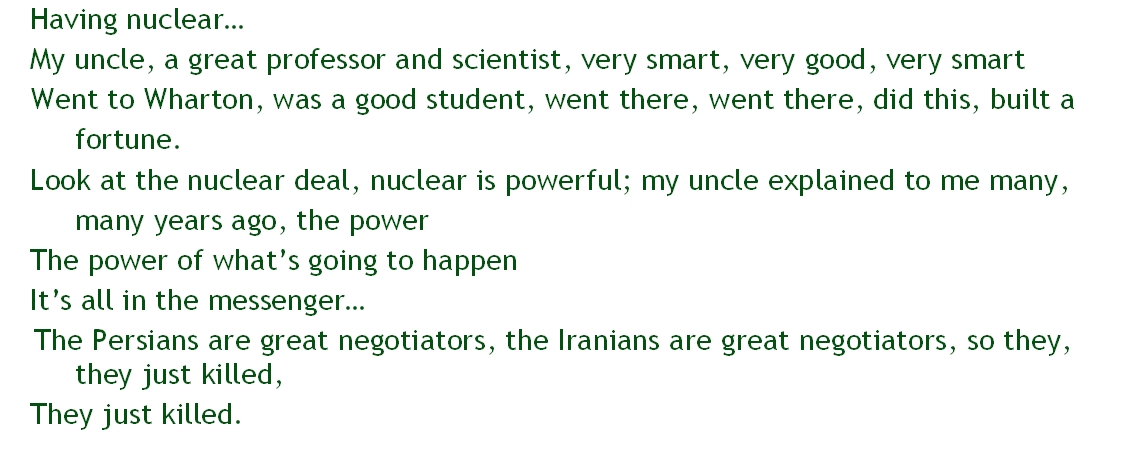

And mine:

Of course I sent both our poems to Sallie. Her response:

Winkie’s made me cry. Yours seems to me to be about chilling killing power. She turns it to the personal. They just killed us. . . You wrote from the viewpoint of the man as cold killer, and Winkie wrote from the viewpoint of the victims.

What?? was my reaction. Never having intended anything like that, I asked for clarification.

Yours is a man bragging, “smart, very smart, etc.,” connecting himself with past brilliance. Then the voice slides into nuclear stuff. And power. The forces he speaks of used their intelligence and their power to kill—and as in dreams, these fragmentary statements are about the self of the speaker. He is a cold killer. He is also blaming others.

Winkie’s starts with the same brag, then onto the power, and she begins to slip into the voice of the victim, I think, with the line “These lives are powerful, explain the power of what’s going to happen . . . ” and steadily grows into the new voice, the victims’ voices, the prisoners’, to “they are killing us.”

I created my found poems, this one included, based purely on instinct—or intuition, or a kind of ear—without thinking too much. If I thought anything, it was that I was distilling an essence of Trump. It was more about the rhythm or the music of the language, his stream-of-consciousness thought process and his repetition, than about concepts. There’s something so destructive of clear cognition in the way he uses language. So I told Sallie it was startling to receive such a specific conceptual interpretation.

She responded:

When a reader finds something one has done “purely by instinct” to have a meaning one hasn’t intended, it has more credibility than if you had had a conscious vision and the reader is seeing something else.

So naturally I asked Winkie what she herself saw in her Trump poem. “I look for rhythm first and then sound,” she told me. “The language was so abrasive. I like to change the tone to give a new feel, so I think it did take on a more victim tone, but I didn’t have the word ‘victim’ in my head.”

You can see why we make such a successful mentor/mentee pair.

This experience of producing poetry made me think about how we produce meaning. My normal mode is writing nonfiction that requires deep, intensive thinking to make a point or argument clear. I think linearly—a mind map makes me dizzy. (That’s why the one above is so feeble. Besides, it’s ex post facto.) Nevertheless there’s a lot of intuition in my writing process: it’s by listening to the rhythm of the sentences that I determine whether I’ve really said what I mean. But in these found poems that’s all I listened to. And if I created meaning, it was one I was unaware of (not something you could say about my books). So is that a different degree/type/level of meaning?

Thank you for this wonderful response! WordPress has stopped notifying me of comments, so I just saw it.

It makes me think more about meaning. There is meaning in the rhythm of my sentences, which convey a mood, just as there is in the visual rhythms you create in your visual art.

I was surprised and pleased that you write in a similar way I create art.

To quote and paraphrase you:

I create my art based purely on instinct—or intuition, or a kind of unconsciousness —without thinking.

“If I created meaning, it was one I was unaware of.”

I feel I am successful if the viewer sees something personal in my pieces, often things I never thought of.

Wonderful stuff, both of you. Now you should try your hands with the Swedish statement!